DAVID LUMSDAINE: A biographical appreciation

© Nicola LeFanu, 2012

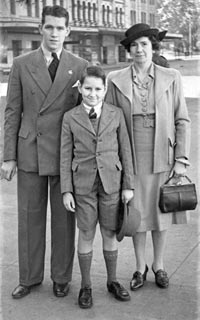

DL, Sydney, 1935.

Born in Sydney in 1931, David Lumsdaine was educated at Sydney University and the N.S.W. Conservatorium. In 1953 he went to England to study with Mátyás Seiber, and, at the Royal Academy of Music, with Lennox Berkeley. In the 1960s he was immersed in English contemporary musical life and established his career there with such works as Kelly Ground, Flights, Mandalas 1 and 2. This led to university appointments, first at Durham (where he founded and directed the Electronic Music Studio, and where he was awarded a D.Mus.) and subsequently at King's College, London. He gradually withdrew from direct involvement in the organisations of the musical world and retired from teaching in 1992.

In 1973 Lumsdaine returned to Australia, and ever since his life has been divided between the two countries. Over the next twenty-five years he composed a body of strikingly original music, commissioned and played by leading ensembles throughout the world. At the same time, he became increasingly engrossed by field recording; chiefly, though not exclusively, of birdsong.

Although Lumsdaine has spent much of his adult life working in the U.K., his ties with Australia remain, spiritually and musically, strong. His music embodies all that is important to him in the Australian landscape – its shapes and rhythms, its creatures, its sudden violence, its sense of unlimited space. His passion for the natural world and its conservation expresses itself more literally in his archive of recorded birdsong.

David Lumsdaine was born on October 31st., 1931, and his early childhood was a happy one. He came from an old Australian family: pioneering farmers on his mother's side, professional people on his father's; both families had come to the colony in the 1820s. DL lived with his parents and two elder brothers in Paddington, in the heart of Sydney. At that date, it was still a city the size of Joyce's Dublin; a city where people recognised you everywhere and knew what you were up to. It was also a city having to come to terms with the poverty caused by the depression, and with the first wave of refugees from Hitler.

DL’s childhood was only partly spent in the city, for long visits were spent on his relation's farms; distant country properties where he first knew the immensity of the Australian landscape and the marvellous, teeming life of the bush. This, above all, was home ground.

His musical gifts were apparent to his family from the beginning: from the age of about four he played the piano by ear - everything he could, whether inventions of his own, or attempts to recreate what he heard. Music meant first, family singsongs; then piano lessons, then lessons at Sydney Conservatorium. Like his brothers, DL won a place to Sydney High School and there, in Gordon Day, he found the first music teacher who could give him the musical nourishment he needed. Day introduced him to the music of the twentieth century, and encouraged him to go on composing.

Geoffrey, David & Marjorie Lumsdaine, Sydney 1942.

When DL was ten, his father died of cancer after a protracted and painful illness. Childhood stability was shattered: the city house was sold, his brothers (James, later a solicitor, and Geoffrey, who became a gifted architect), went straight from school to the war. DL's solace was to go bush: solitary walks, sleeping out overnight, steeping himself in sounds and smells and textures and getting to know every bush creature.

When he emerged from adolescence it was as a restless, questing person; radical in politics and void of the conventional Christianity in which he had been brought up. Like so many of his contemporaries, he found the bourgeois white Australia of the late forties, unbearably constricting. Nevertheless, these years were not wasted ones. Under the direction of Eugene Goossens, the Sydney Symphony Orchestra played a repertoire which ranged right across the twentieth century. DL attended all the rehearsals he could, avidly studying the scores: Ravel and Stravinsky, in particular. At the same time he was discovering a tradition of family chamber music, through his friendships with Jewish immigrants from central Europe. Although by now the hours spent composing meant that piano practice was almost always forgotten, DL did not neglect piano playing: Mozart and Schubert, Bach, and often, jazz.

Simultaneously a student at Sydney Conservatorium and a general arts student at Sydney University, DL became engrossed in theatre, in philosophy, he discovered a lifelong passion for anthropology, and formed alliances and friendships with many of the men and women who were later to play an important part in changing Australian society. Within his family, he became closer to his cousin, Hal Wootten, who later became one of Australia’s most eminent jurists, committed to the cause of Aboriginal rights and, later, a leading conservationist; it was a relationship which would flower following Hal’s visit to Britain in 1970, and DL’s return to Australia in 1973.

DL graduated in 1952, though it is not easy to see where, with all his extra-curricular activities, he made the time for study: by night he was a tram conductor, to supplement his university scholarship; and he composed without ceasing, producing a number of orchestral works as well as a succession of chamber pieces and songs.

Composing was as natural to him as dreaming or breathing, but he had some insight into the nature of the journey he needed to make in order to truly realise his vision. It would have to be both an inward journey of self-discovery and a literal journey: which he undertook in 1953 when he left Australia to study in England with Mátyás Seiber.

Lumsdaine's letters home to his mother paint a vivid picture of musical life in London in the early 1950s. Outstanding among his early impressions were performances by Britten and Pears, of Purcell, Bach and Schubert as well as new works of Britten. DL found the London orchestral repertoire less adventurous than that of Goossens, but the general cultural life of a European city was enthralling, as were his new friendships with writers, journalists and artists, as well as musicians. Some months after his arrival he met his compatriot, the poet Peter Porter, and they remained friends till Porter’s death in 2011. There are many anecdotes of their early friendship. Both were more or less penniless; they earned their suppers through P.P.'s brilliant talk and caustic wit, and DL's repertory of bawdy songs. Marie de Lepervanche, another close friend, has recalled the occasion when DL invited Ian Hogben, the eminent Australian anthropologist, to dinner one winter evening. As neither PP nor DL could afford heating, their flat was perishingly cold; PP's precious collection of New Statesman was sacrificed as fuel, and the four of them, wrapped in blankets, huddled round the small fire in the open grate.

The many collaborations PP and DL made began at this time, including a series of cantatas, and a number of attempts at operas: on the Children's Crusade, on Voltaire's Candide and on Ned Kelly. Most of the material was afterwards lost or destroyed, though some of the later cantatas have survived: Temptations in the Wilderness, Story from a time of Disturbance (MSS of both viewable in National Library of Australia), and Annotations of Auschwitz.

Of the many musical friendships DL made, the closest were with Anthony Gilbert and Don Banks. The latter had left Australia to study with Dallapiccola and was already well established in Britain; they had many musical interests in common (not least, jazz) and remained friends until Banks' untimely death.

After a year or so in London and Madrid, DL moved to Surrey so as to be closer to Seiber, and settled down to study in earnest. The lessons were in analysis, harmony and counterpoint, moving on later to composition proper. He found in Seiber's teaching the discipline he had missed in Sydney, and felt that at last he was coming to grips with compositional technique.

To support himself, DL worked initially as a schoolteacher, gradually moving on to general freelance musical work: conducting, teaching, lecturing and so on. His passion for the natural world began to express itself in studies of birdsong, and he made his first forays into the world of wildlife sound recording. Another characteristic preoccupation was his work in the peace movement. DL was a member of the Direct Action Committee, an original member of the Committee of a Hundred, and his tireless involvement with the early groups working for nuclear disarmament ended on more than one occasion in arrest and imprisonment.

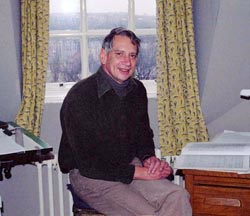

DL at ‘Paddocks’, Great Bookham, Surrey, 1964.

Throughout the fifties and early sixties DL drove himself relentlessly as a composer, sketching, composing, destroying work and beginning again. As far as the quality of his own work was concerned he was much more than is implied by the word perfectionist. He was an idealist, who saw no point in releasing works that might have been composed by someone else. Virtually nothing survives of the enormous body of work composed before 1964.

One might say that he was ruthlessly ambitious for his own muse, but utterly without worldly ambition. It was then, as now, foreign to his nature to seek out 'contacts', to take care to be in the right place at the right time, or to go in for any of the ruses by which young men usually promote their careers. As Louise Varèse said of her husband ‘he was as uncalculating as a little child’ and DL proved incapable of self-promotion.

Very gradually, however, the music began to attract attention; for example the Variations for Orchestra, the Short Symphony, and the cantatas to texts by Porter. As DL approaches maturity in these works, the polarities of his musical background are strikingly apparent. On the one hand is his new understanding of European music: he uses post-serial procedures with ease; and in the canonic writing, the counterpoint and the control of line in the larger voice leading, it is clear how fruitful his studies with Seiber had been. On the other hand, the rhythmic characterisation and the formal shapes of the music show that he was already creating a musical imagery quite unlike anything in European new music.

With hindsight, we may say that it is not just the years of study that were bearing fruit, but the years spent as a child with ears attuned to Australia's unique soundscape: the rhythms of the Pacific breakers which he heard from his bedroom window; the density and brilliance of the birdsong; the sound of wind travelling across mile after mile of outback country.

None of these things have a literal place in DL's musical language, which is in no way programmatic. Together, they led him to a radically different way of thinking about music: about alternatives to European models of musical syntax, musical causality. Most crucially, they led him to an altered perception of time: DL began to explore new ways of relating time and musical space and over the next twenty years dedicated himself to forging an appropriate rhythmic and harmonic language to realise these ideas. In the extraordinary succession of works he produced, certain compositions stand out as milestones along the way: Kelly Ground (1966), Aria for Edward John Eyre (1972) Hagoromo (1977) Mandala 5 (1988). In Kelly and Aria, Australian mythology is allowed into the foreground; in the two orchestral works it is subsumed.

The 1960s were hectic free-lance years for DL. An active committee member of the SPNM, he founded, with Don Banks and Tony Gilbert, the annual Composers Weekends that brought together composers and performers of all ages. The Weekends flourished for over twenty years, supporting many emerging composers as well as bringing distinguished international figures to the UK. At the Royal Academy of Music he founded the Manson Room, a resource centre for composers; he enjoyed the intense dialogues with other composers, not only on music, but ranging across the arts and other disciplines. It was at this time that many younger composers began to seek him out, John Tavener notable among them.

DL by Salvation Creek, Kurringai Chase, NSW, 1976.

All this led naturally to his appointment (1970) to a lectureship at Durham University. Here he threw himself into building support for new music. He chaired the Music Panel of Northern Arts, started the University’s concert series, Musicon, and embarked on establishing composition and the performance of new work in the Music Faculty. Durham thus became one of the first UK universities to offer a PhD in composition. Those who came to work with DL and went on to make their mark in the musical world included Peter Wiegold, Michael Clarke, Robin Walker and Jane Wells as well as younger students such as Helen Roe. With his first PhD student, Peter Manning, DL founded Durham’s Electronic Music Studio (EMS); together with technician Ron Berry, their research soon established it as a leading resource. Meanwhile DL’s music was being more widely performed, in particular through the support of the BBC. Returning to Australia, and doing so more frequently, his music became established there too. The seventies were productive years: Ruhe sanfte, sanfte ruh' (solo piano), and its metamorphosis in the chamber work Mandala 3; Salvation Creek, Sunflower (both for chamber orchestra) and Hagoromo (for the Proms, BBCSO) are all remarkable works from this decade. Many close musical relationships were cemented: Elgar Howarth, Jane Manning, Barry Guy, Ron Lumsden, Peter Wiegold, Ian Mitchell and at the BBC, Michael Hall.

DL, Hatfield College, Durham, 1979.

From 1981 to 1992, DL and I shared a joint post at Kings College London. Here DL once again created a PhD programme in composition, attracting many overseas postgraduates, including Andrew Schultz, Richard Gibson, Joyce Koh, Daphne Teo and Hoh Chung Shi, who later became leading composers and teachers in their own countries.

This was also the time that saw the burgeoning of DL’s activity as a field recordist. Moving beyond his research into birdsong, he began recording broad soundscapes, usually captured at first light and through the dawn; these were edited with scrupulous attention to their temporality and acoustic. Thanks to the championship of the ABC and of Belinda Webster (founder of the Tall Poppies CD label), his soundscapes became widely available.

This era saw the composition of further substantial orchestral works: Mandala 5 was written for the Sydney Symphony and Stuart Challender, a conductor who, like Howarth, had a special understanding of DL’s music. A Garden of Earthly Delights (1992) followed, a cello concerto (also with SSO and Challender) written for David Pereira, another close musical colleague. In the UK, the span of works from Cambewarra (1981, solo piano) to A Tree Telling of Orpheus (1990, soprano and chamber ensemble) demonstrated the breadth of DL’s mature idiom.

In the works of his maturity DL achieves the technical mastery he had sought so long. He moves effortlessly in an harmonic/rhythmic language of great complexity, and through it he discovers the directness of expression, the translucency, which is a hallmark of his work. The complexity lies behind the music, so the listeners need never be aware of it: rather it is the structure which allows the music to flower and proliferate in Lumsdaine's dancing textures; it is the means by which the music attains a shimmering radiance all its own.

It is hard to reconcile the achievements of these works with their neglect. DL’s music has never lacked for musicians who wish to commission and perform it, or for professional colleagues who are passionate advocates of the music; but it has been largely ignored by musical establishments for the latter part of his lifetime - perhaps a reflection of a mutual disregard. Yet to be unperformed is a kind of death for a composer.

DL has often spoken of how music is a social art, an act of celebration; it exists only in performance, a score being merely an aide-memoire. To speak of DL composing effortlessly could be misleading: there have been many times when black despair made it seem impossible that the next work would ever be written. Yet suddenly, seemingly without warning, the next work would emerge, unscathed and triumphantly itself; and at this point the fluency and speed with which DL composed - straight into fair score - had to be seen to be believed.

During the nineteen-nineties there were a series of major changes in DL’s life, some positive, some negative. His retirement from teaching (he had already left all the committees and public bodies on which he had served so tirelessly) paved the way for a flowering of late works, notably A Norfolk Songbook (1992) and Kali Dances (1994). Yet most of the works of the nineties are epigrammatic or aphoristic; they are both a measure of DL’s long commitment to Zen meditation, and a reflection of increasing problems with composing and with physical hearing.

In Lappland, 2007.

From around 1997 DL ceased composing, saying that ‘he had not retired, but his muse had retired him’. It was a desolate situation for someone who had lived his whole life as a musician. For the next decade, DL found his creative outlet through wildlife sound recording, making many trips to remote outback Australia to capture undisturbed soundscapes before the noise of the twenty-first century overtook them. Many of the soundscapes were published on CD; recordings such as The Pied Butcher Birds of Spirey Creek were frequently broadcast and brought his name to a wide audience. His archive of over three thousand recordings is held in the British Library’s National Sound Archive, much of which can be accessed online.

As DL reached his eightieth year in 2011, new CDs of his music appeared, including the electro-acoustic poem Big Meeting, composed in 1977 and based on 1971 recordings of the famous Durham Miners’ Gala. DL’s hearing problems were now profound, and he worked with Craig Vear on the re-mastering, as well as on Dusk Chorus, the commission (for surround sound and dance) he undertook for the 2011 City of London Festival. Michael Hooper, who had become an authority on Lumsdaine, published his analytic study The Music of David Lumsdaine, Kelly Ground to Cambewarra (Ashgate, 2012); Michael Hall’s monograph Between Two Worlds: The Music of David Lumsdaine (Arc) had appeared in 2003.

Despite his identification with Australia, DL’s family life has been based in England: Surrey, Durham, London and currently York. He has been married three times: to Margery Van Clute in 1955, to Edna Perry in 1969, and to myself in 1979. He has three children: Sarah Lumsdaine Parr (b 1970), the mother of his grandchildren; Naomi Lumsdaine (b.1971) a barrister, and like her father, a human rights activist; and Peter LeFanu Lumsdaine (b.1982), a research mathematician.

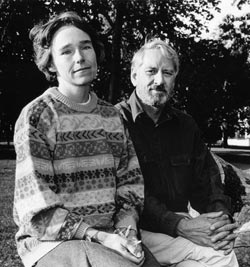

Nicola LeFanu and DL, Queens Park, London, 1990.

I first knew DL and his music in 1972, when he was writing Aria for Edward John Eyre. This work was an overwhelming experience for me, as it was for a number of other young composers, and it rapidly acquired the status of a myth, with tape copies circulating like samizdat. The intellectual prowess of the piece was awe-inspiring, but it was the sensuous physicality of the music that impressed us first and last: the fecundity of the rhythmic imagination, the richness of the harmonic palette, the ever-changing textures; maybe wild, extreme, demanding virtuoso performance technique; maybe gentle, inward, tiny details as telling as the grandest gesture.

Looking back over the forty years that have elapsed since Aria, I feel something of what Louise Varèse must have felt as she contemplated writing her husband's biography. However, I have the advantage of also being a composer, and I trust my judgement of this music absolutely. The world may never have much time for someone so unworldly as DL; but as the wheel of musical fashion comes around, his music will take its rightful place in the hearts and ears of musicians and audiences.

It has seemed necessary to set on record something of the paradoxes of achievement and neglect in Lumsdaine's career - a man for whom the words 'making a career' have, in the conventional sense, no meaning. Lumsdaine's ambition was solely to discover the musical language which could begin to express the music of his dreams.